Disrupting the Narrative: How Sadaf Sadri Reimagines Traditional Systems in De/Angular

“When I was growing up in Tehran, I had this very good friend whose father was a painter, so I spent time in their house, immersed in that sort of environment—an artist’s studio and his paints and all that. No one in my family makes art of any kind, so [being in this friend’s house] must have been an influence.”

Like many young people, Sadaf’s mother recognized their strength in left-brain subjects like math and physics and instead directed Sadaf to pursue a lucrative career, like engineering. Yet Sadaf was drawn by the irresistible pull of creative pursuits—and visual expression, specifically.

“I didn’t have access to a lot of high art, like galleries or museums. But I grew up watching a lot of music videos. I think that’s how I got interested in cinematography.” Sadaf was drawn to the medium because lighting, sound, and other visual effects helped tell such compelling and irresistible stories.

Sadaf studied cinema at University of Tehran before attaining an MFA in Photography and Media at University of Washington, where they’re currently pursuing a PhD. Along the way, Sadaf began to realize the power of art, cinematography and new media to play a role in advancing social justice and human rights by imagining and demonstrating alternate perspectives or different outcomes or endings.

“Wherever you grow up and recognize discrimination and injustice—especially if you are some kind of minority—it affects you. And at some point I decided I needed to say something about it, to do something about it.”

Like so many, Sadaf’s awakening to injustice began from a place of anger, which they recognized and wanted to make good use of. “And [at first] you don’t know how to do it. I began thinking about Iran and the Islamic Republic and realizing that the oppression was the result of patterns that have been repeating.”

Sadaf recognized the potential to disrupt conventional thinking about injustice by imagining something different and new through art and digital storytelling.

“I was in the studio one day when I was getting my Masters, and I began thinking about the beautiful stained glass used in mosques. I had this idea of literally disrupting the patterns [to achieve something new and different].” Using sheets of plastic, Sadaf began to work on reimagining the patterns and recreating the system all over again. What emerged was a criticism of patriarchy through a traditional, almost taken-for-granted art form—in this case the dazzling stained glass used in traditional places of prayer and worship.

Sadaf notes that often, such traditional forms of art “are constellations of meaning, being used as propaganda to sustain a system [of belief]. So, I was like—I’m going to disrupt this.”

Jump cut to the current installation at Gallery 4Culture, De/Angular. In the statement about the show, Sadaf recounts a story about her grandmother, a devout follower of Islam, and a man who would come to the house when Sadaf was a child to read the Quran. Sadaf’s name indicates that they’re a descendant of the Prophet. Same with the man who would come to the house to sing and pray and cry— a man her grandmother identified as “a good, and real, descendant of the Prophet,” as a way to make a contrast with what she believed Sadaf was not.

“She wasn’t wrong,” Sadaf has said. “I’m an eccentric in my ancestral house—a queer woman— and no one knows if I’m a descendant of the prophet or not. I think it’s a myth, a story. So for this show, I decided to disrupt the myths. To strip original meanings away. To remove traditional iconographies of the prophets and all the other boys, but keep the framework and the structure” and, in doing so, to put alternative ways of thinking and new mythologies in their place.

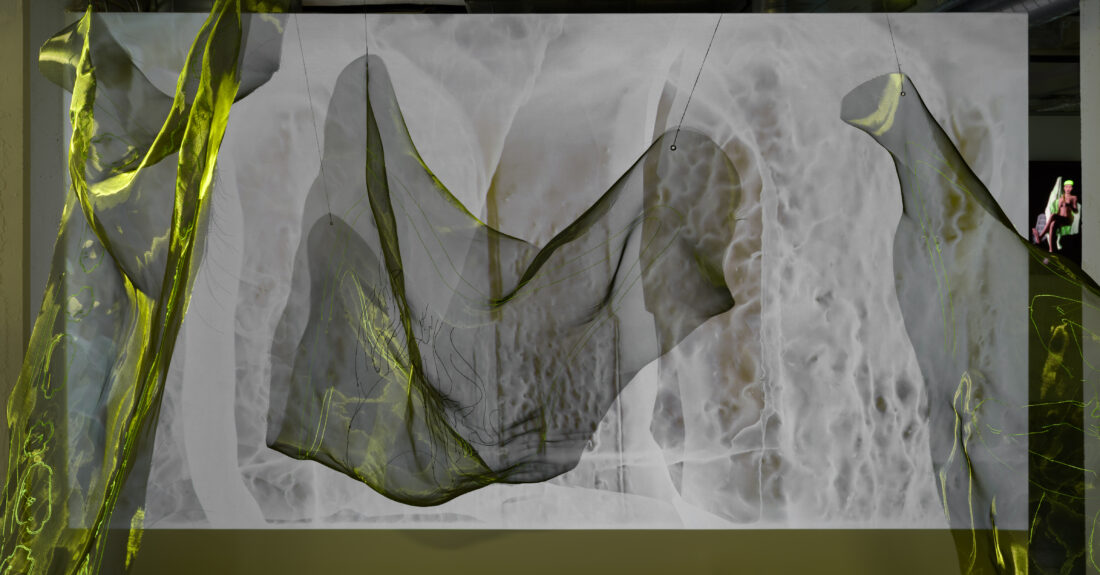

The result is artwork that leans into traditional Shia iconography, recreated with materials that are fragile; materials that might not hold the original myths with which they were imbued. “I looked at Islamic patterns and iconography and recreated them—digitally or with alternate materials—replacing traditional iconography with figures and entities that had been erased.”

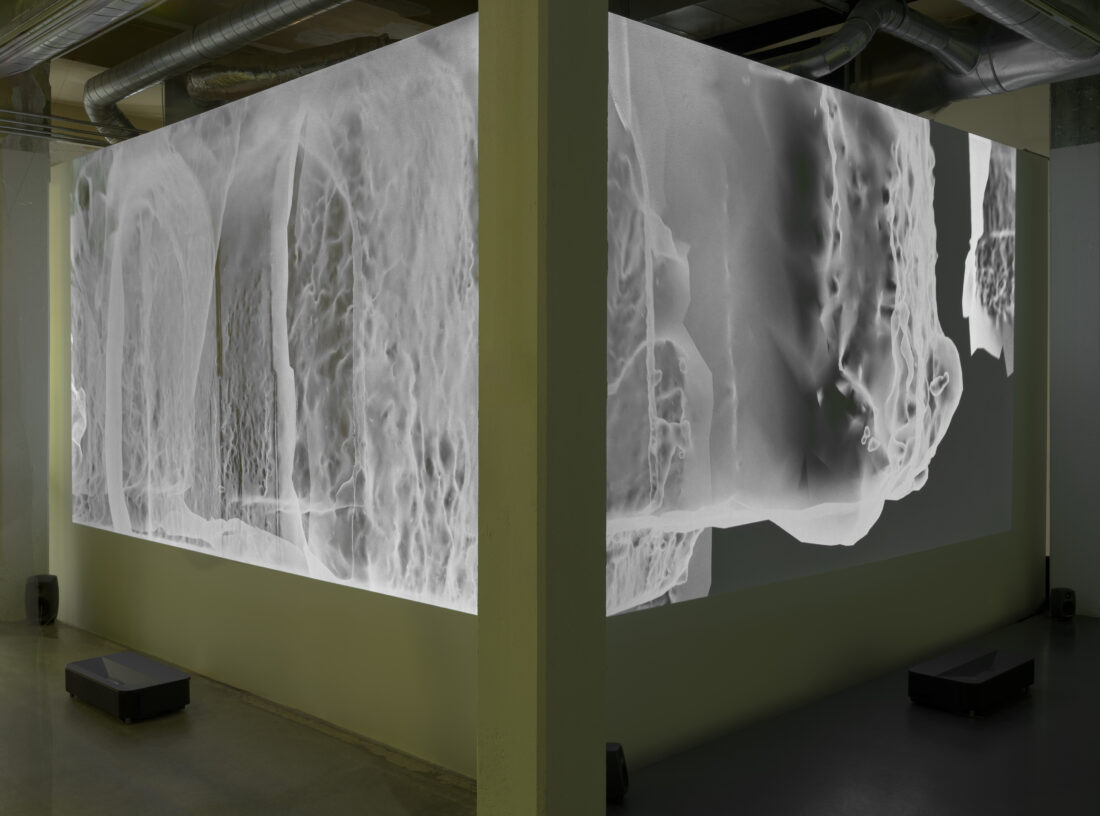

We see this in the projections on adjacent walls which create a virtual re-interpretation of the Great Abbasi Mosque in Isfahan, Iran. “I’ve been working with this mosque a lot,” Sadaf tells us. “I’ve been interested in it because of my memories and the impact its scale has had on my body, but also because of its inaccessibility to me at this time and in this queer existence.” Sadaf explains they’re interested in the physical structure of the mosque as the manifestation of a particular system of governance, and how that space dictates the movement and placement of one’s body, and dictates what is private and public. For this specific show, “I have attempted to make the architecture more translucent and soft… to imagine that if the architecture was made of soft materials, every movement would change its meaning and create new narratives.”

Across the gallery, small tablets line the largest wall, and the face of Sadaf’s avatar is present on each of them, reciting spells. There is an interactive component where the visitor touches fabric hands which causes audio of the spells to play through the speakers. “So there is a constant whispering going on with a call to prayer. One can only clearly hear the spells when they physically connect to the entities with their hands.” Sadaf notes that they’re inspired by entities in Iranian folklore and that each avatar and its accompanying spell is a vessel to help visitors connect to the wisdom of each character.

Much of the work in De/Angular, and Sadaf’s body of work in general, is intended to place traditional forms in different contexts, to disrupt the narratives we take for granted and invite viewers to consider alternative ways of seeing or believing. It’s about being open to complexity and asking people to look at things in a different light and ask questions. And it poses the question that guides Sadaf’s academic research: can the very mechanisms that empower a system to maintain dominance be reappropriated, thus instigating disruption within that same system?

“I’m a small person. And this is a small show. But I think my hope is to make it easier [for people] to see something else by taking things in a different context. It’s hard. It’s a lot of work to imagine something that’s not in front of you, or think of something you haven’t seen or experienced… It’s hard to go against the flow of [known] things.

“So the hope for me is to make it easier to imagine.”

De/Angular is on view through February 20. Join Sadri on Thursday, February 5 from 6-8 pm for the Pioneer Square Art Walk and for an Artist Talk Friday, February 20 from 6-7 pm. No registration is required to attend.